Adventures into underworld mazes are the most popular. The party equips itself and sets off to enter and explore the dungeons of some castle, temple or whatever. Light sources, poles for probing, rope, spikes, and like equipment are the main tools for such activity.

I think the equipment Gygax mentions by name is telling: not weapons or armor but torches, poles, rope, and spikes. This is indeed an "expedition," as he terms it elsewhere, one on the model of archeological excavations or perhaps the Victorian adventure tales of H. Rider Haggard (or even "The Tower of the Elephant").

And since none of the party will know the dungeon's twists and turns, one or more of the adventurers will have to keep a record, a map, of where the party has been. Thus you will be able to find your way out and return for yet more adventuring. As you party is exploring and mapping, movement will be slow, and it is wise to have both front and rear guards.

Do RPG campaigns regularly include a mapper anymore? In my youth, it went without saying that someone should be keeping a map. Otherwise, as Gygax says, how would you find your way out again – or, just as importantly, take note of unusual features that suggested there might be hidden chambers nearby? In my House of Worms campaign, the players are blessed to have a professional cartographer in their company, but, even if they didn't, I'm pretty sure they'd keep track of the underworlds they explore.

In the dungeons will be chambers and rooms – some inhabited, some empty; there will be traps to catch those unaware, tricks to fool the unwise, monsters lurking to devour the unwary. The rewards, however, are great – gold, gems, and magic items. Obtaining these will make you better able to prepare for further expeditions, more adept in your chosen profession, more powerful in all respects. All that is necessary is to find your way in and out, to meet and defeat the guardians of the treasures, to carry out the wealth …

That's a very succinct way of describing the gameplay of Dungeons & Dragons, don't you think? More than that, it also draws our attention to the things Gygax considered the essential elements of a dungeon: rooms (including empty ones), monsters, treasure, traps, and tricks – a good list!

Adventuring into unknown lands or howling wilderness is extremely perilous at best, for large bands of men, and worse, might roam the area; there are dens of monsters, and trackless wastes to contend with.

The wilderness is where Gygaxian naturalism lives – literally – hence the following admonitions:

Protected expeditions are, therefore, normally undertaken by higher level characters. Forays of limited duration are possible even for characters new to adventuring, and your DM might suggest that your party do some local exploration – perhaps to find some ruins which are the site of a dungeon or to find a friendly clan of dwarves, etc.

One "problem" with D&D, it's that the wilderness surrounding a dungeon is frequently far more dangerous than the dungeon itself, given the lack of an artificial level-based framework for assessing threat to the characters. Gygax's comments here remind us of that.

Mounts are necessary, of course, as well as supplies, missile weapons, and the standard map-making equipment. Travel will be at a slow rate in unknown areas, for your party will be exploring, looking for foes to overcome, and searching for new finds of lost temples, dungeons, and the like.

Once again, mapping and slowness are mentioned – but then D&D is primarily a game of exploration. Nevertheless, Gygax quickly notes that that's not all the game is about.

Cities, towns, and sometimes even large villages provide the setting for highly interesting, informative, and often hazardous affairs and incidents. Even becoming an active character in a campaign typically requires interaction with the populace of the habitation, location quarters, buying supplies and equipment, seeking information.

Though not intended as such, these sentences could serve as a rebuke of critics who deride D&D as a purely "hack 'n slash" game. Some of my favorite moments in D&D (and other RPGs) have arisen from interactions with NPCs in a settlement as the characters sought out rumors, lodging, or equipment.

These same interactions in a completely strange town require forethought and skill. Care must be taken in all one says and does. Questions about rank, profession, god and alignment are perilous, and use of an alignment tongue is socially repulsive in most places.

Everything Gygax says here demonstrates the need for the creation of a social structure and culture for the campaign setting. Without these, there can be no context for adventures and many opportunities for fun interactions will be missed.

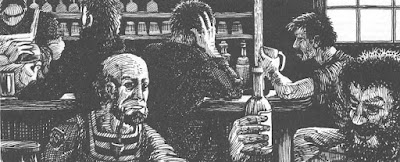

There are usually beggars, bandits, and drunks to be dealt with; greedy and grasping merchants and informants to do business with; inquiring officials or suspicious guards to be answered. The taverns house many potential helpful or useful characters, but they also contain clever and dangerous adversaries. Then there are the unlit streets and alleys of the city after dark …

If this section has made anything clear, it's that, in a good campaign, adventures can be found anywhere.

0 Yorumlar